Lo siento, hoy te suelto un ladrillo en inglés. El tipo es un economista muy sensato y comenta un poco todo…

Michael Pettis explains the euro crisis (and a lot of other things, too)

This is literally the best analysis of the euro area's problems we've ever read. You should take the time to closely read the whole thing yourself. We'll wait.

Now that you're back, we thought we could add some value by highlighting and expanding on what we believe to be Pettis's most important insights.

First, the relevant units within the euro area aren't countries but economic sectors. For all of the suffering that has occurred in places such as Spain, Ireland, and Greece, we shouldn't forget that German workers have suffered from stagnant wages and decaying infrastructure.

One of the worst costs — for Germany — has been the lack productivity growth. For all the talk of Teutonic competitiveness, German labour productivity has grown at the meagre pace of just 0.6 per cent per year, on average, since 1998. Output per hour worked is actually lower now than it was in 2007. For perspective, this track record is worse than that of practically every other rich country — including Greece and Spain!

The right distinction, therefore, isn't between countries but between classes (emphasis ours):

It was not the German people who lent money to the Spanish people. The policies implemented by Berlin that resulted in the huge swing in Germany's current account from deficit in the 1990s to surplus in the 2000s were imposed at a cost to German workers, and have been at least partly responsible for Germany's extremely low productivity growth — most of Germany's growth before the crisis can be explained by the change in its current account — rather than by rising productivity.

Moreover because German capital flows to Spain ensured that Spanish inflation exceeded German inflation, lending rates that may have been "reasonable" in Germany were extremely low in Spain, perhaps even negative in real terms. With German, Spanish, and other banks offering nearly unlimited amounts of extremely cheap credit to all takers in Spain, the fact that some of these borrowers were terribly irresponsible was not a Spanish "choice."

I am hesitant to introduce what may seem like class warfare, but if you separate those who benefitted the most from European policies before the crisis from those who befitted the least, and are now expected to pay the bulk of the adjustment costs, rather than posit a conflict between Germans and Spaniards, it might be far more accurate to posit a conflict between the business and financial elite on one side (along with EU officials) and workers and middle class savers on the other. This is a conflict among economic groups, in other words, and not a national conflict, although it is increasingly hard to prevent it from becoming a national conflict.

Ironically, the biggest political beneficiaries of the crisis (so far) haven't been pan-European socialists, but nationalist movements of both the right and left.

Second, when it comes to big flows of capital across borders, it's usually better to give than to receive. The basic problem is that huge inflows of money are almost never matched by commensurate increases in the number of profitable investment projects, so a ton of money gets wasted on boondoggles, usually related to real estate. That ends up boosting wages without increasing productivity. That lowers competitiveness and worsens the trade balance, which makes it harder to service foreign debts even as the obligations pile up.

(Borrowing in a currency you can print is helpful but it doesn't prevent a lot of resources getting misallocated and a lot of people ending up with excessive debt burdens.)

It's easiest to see how this all adds up in the case of Spain. According to Eurostat, a whopping 20 per cent of all the jobs created in Spain from 1998 through 2007 were construction jobs, even though construction accounted for a little less than 10 per cent of total employment in 1998. The result was zero growth in labour productivity in that period. (The building industry is notorious for its falling productivity, as Cardiff has noted.)

Now look at what happened to Spain's capital imports, as shown by comparing its current account balance to global GDP:

(Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database on GDP and current account balances, author's calculations)

At the height of the bubble, Spain — a mid-sized economy in Europe that was home to only about 45 million people — was importing more capital than every other country in the world except for the United States. Also note that Greece — a country of just 11 million people — was the fifth-most dependent on foreign creditors:

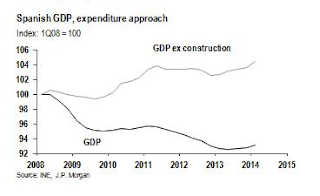

In addition to reducing productivity, the lending that enabled the Spanish construction boom also led to a lot of overbuilding. The subsequent cutbacks to deal with the inventory overhang have crushed employment and GDP. Had it not been for those cutbacks, Spain's economy would actually have done pretty well. Via JPMorgan:

Pettis illustrates this brilliantly by looking at what happened to the German economy after it received reparation payments from France following the Franco-Prussian war:

From 1871 to 1873 huge amounts of capital flowed from France to Germany. The inflow of course drove the obverse current account deficits for Germany, and Germany's manufacturing sector struggled somewhat as an increasing share of rising domestic demand was supplied by French, British and American manufacturers.

But there was a lot more to it than mild unpleasantness for the tradable goods sector. The overall impact in Germany was very negative. In fact economists have long argued that the German economy was badly affected by the indemnity payment both because of its impact on the terms of trade, which undermined German's manufacturing industry, and its role in setting off the speculative stock market bubble of 1871-73, which among other things unleashed an unproductive investment boom and a surge in debt.

The party ended with the start of the Long Depression in 1873. As boom turned to bust, views on the merits of reparations changed:

Within a few years of the beginning of the crisis attitudes towards the French indemnity had shifted dramatically, with economists and politicians throughout Germany and the world blaming it for the country's economic collapse. In fact so badly was Germany affected by the indemnity inflows that it was widely believed at the time, especially in France, that Berlin was seriously contemplating their full return. The great beneficiary of French "largesse" turned out not to have benefitted any more than Spain had benefitted from German largesse 135 years later.

Third, it makes no sense to blame the recipients of the capital inflows for causing the crisis. If enough money is sloshing around willing to invest in any stupid idea, you shouldn't be too surprised that a lot of stupid ideas get funded. When, for example, Wolfgang Schaeuble, Germany's finance minister, says:

The reasons for Greece's problems can be attributable only to Greece and not to actors outside the country, and certainly not in Germany.

As he did during the press conference following his meeting with Yanis Varoufakis, his Greek counterpart, we have to remember that Schaeuble is talking nonsense. It's logically impossible for excess borrowing to occur unless there is someone sufficiently reckless (or stupid) to provide the financing.

The problem with Schaeuble's assignment of blame is that it prevents optimal solutions that are best for the majority of Europeans, Greek, Spanish, and German alike. Pettis:

An awful lot of Europeans have understood the crisis primarily in terms of differences in national character, economic virtue, and as a moral struggle between prudence and irresponsibility. This interpretation is intuitively appealing but it is almost wholly incorrect, and because the cost of saving Europe is debt forgiveness, and Europe must decide if this is a cost worth paying (I think it is), to the extent that the European crisis is seen as a struggle between the prudent countries and the irresponsible countries, it is extremely unlikely that Europeans will be willing to pay the cost.

In fact, Pettis thinks that, if anything, it was net lenders in Germany and the Netherlands who were responsible for what happened, rather than borrowers in Ireland or Greece or Spain:

It would be an astonishing coincidence that so many countries decided to embark on consumption sprees at exactly the same time. It would be even more remarkable, had they done so, that they could have all sucked money out of a reluctant Germany while driving interest rates down. It is very hard to believe, in other words, that the enormous shift in the internal European balance of payments was driven by anything other than a domestic shift in the German economy that suddenly saw total savings soar relative to total investment.

That shift, in turn, is connected to anaemic wage growth and even weaker domestic consumption in Germany.

Fourth, it matters how your obligations are structured. Many smart people, most notably Daniel Davies, have argued that the headline numbers surrounding Greece's public debt burden are irrelevant to understanding the situation in Greece. As Davies puts it:

The total figure for "Greece's Debt Burden" is an economically meaningless number. Everyone knows it is going to be restructured at some politically convenient time in the future; it simply can't be paid back, and so it simply won't be. So increasing the size of the debt outstanding by 2.5 now just means that you increase the size of the writeoff in the year two-thousand-and-something by the same amount. Concentrate on the flows and only on the flows — the stocks are no longer a useful quantity to think about.

But the focus on flows misses the impact of the structure of the debt stock on the incentives of private sector lenders and producers, writes Pettis (our emphasis):

The face value and structure of outstanding debt matters, and for more than cosmetic reasons. They determine to a significant extent how producers, workers, policymakers, savers and creditors, alter their behavior in ways that either revive growth sharply or slowly bleed away value.

Incentives must be correctly aligned, in other words, so that it is in the best interest of stakeholders collectively to maximize value (this rather obvious point is almost never implemented because economists have difficulty in conceptualizing and modelling reflexive behavior in dynamic systems).

Rather than let economists work out the arithmetic of the restructuring based on linear estimates of highly uncertain future cashflows, whose values are themselves affected by the way debt payments are indexed to these cashflows, Greece and her creditors may want to unleash a couple of options experts onto the repayment formulas and allow them to calculate how volatility affects the value of these payments and what impact this might have on incentives and economic behavior.

This is why Pettis thinks Varoufakis's plan to swap existing Greek debts for obligations indexed to GDP is a good idea that ought to be expanded to other countries, including Spain and Italy. The appeal of these GDP-indexed obligations is that they give creditors an incentive to support investments in future growth.

That's very different from the current setup, where the Troika has every incentive to tie its funding to the willingness to implement austerity programmes. Even if those programmes boosted productivity in the long term by shifting resources away from the state, the behaviour demanded by the euro area's official sector creditors exacerbates the cyclical weakness.

The good news, though, is that a different liability structure that encourages additional investment could instantly lead to stronger growth given the reforms that have already occurred. Moreover, a large-scale restructuring should encourage lots of new investment even if it also wipes out many existing creditors, at least if they are done soon. As Pettis puts it:

There is overwhelming evidence — the US during the 19th Century most obviously — that trade and investment flow to countries with good future prospects, and not to countries with good track records. The main investment Spain is likely to see over the next few years is foreign purchases of existing apartments along the country's beautiful beaches.

Once its growth prospects improve, however, with among other things a manageable debt burden, foreign businesses and investors will fall over each other to regain the Spanish market regardless of its debt repayment history. This is one of those things about which the historical track record is quite unambiguous.

That leads to the fifth point: euro area officials are running out of time. Patience may be a virtue in some situations, but not when it comes to crisis resolution and debt restructuring. That's especially true when you appreciate the difference between "financial crises that occur within a globalization cycle and those that end a globalization cycle."

The past few years have been a golden opportunity for even the dodgiest borrowers to raise capital at low spreads, because the rich world (where most foreign investment comes from) has been awash in savings searching for a decent return. Under current conditions, there would be plenty of investors eager to jump in and finance investment in Greece, Spain, Ireland, etc if they dramatically restructured their debts. Just think of all the "dry powder" burning holes in the pockets of the private equity firms (and their LPs!), or the bond investors searching, but not finding, decent rates of return in their home country. After all, if Ecuador can do it…

Pettis reminds us that it's always been this way. Germany was surprised at how easy it was for France to raise the money necessary to pay its 1871 reparations — a bill worth more than 20 per cent of France's annual GDP. In fact, "the French indemnity actually increased global liquidity by expanding the global supply of highly liquid 'money-like' assets."

The Weimar government also had an easy time securing credit from American and other lenders to cover its own reparations half a century later once hyperinflation had wiped out its domestic debts.

But sometimes the timing is rough. The boom in lending to Latin America funded by petrodollars in the 1970s had a very unhappy ending because the 1980s were a period of relatively high rates in America and Europe, not to mention lower commodity prices. The combination was a disaster for the debtors who had borrowed in dollars.

We at Alphaville have no insight into the future of monetary policy or global liquidity here or in Europe. But we wouldn't be surprised if it turned out that the optimal window for restructuring, even if you leave aside the political implications of persistently high unemployment, could soon close. Something for the can-kicking eurocrats to keep in mind.

Finally — and you should have figured this one out by now — nothing about the euro crisis is particularly new. All of this has happened before and all of it will (probably) happen again. There isn't any need to understand radical new financial products or technological innovations or world-historical changes in politics to figure out why everything blew up. Historical literacy and/or a decent model of capital flows in a fixed exchange-rate system would have been more than sufficient.

In fact, one of our favourite books about finance and economics — Pettis's The Volatility Machine — has basically everything you need to know about the euro crisis even though it was written before the euro had even launched. (The appendix on the relationship between option pricing and credit risk is worth the price of admission alone, in our view.)

No wonder he writes in his latest article that "the current European crisis is boringly similar to nearly every currency and sovereign debt crisis in modern history."

Abrazos,

PD1: El análisis técnico siempre es muy difícil de hacer, pero sirve ver los gráficos para darnos una idea. En España, el Ibex es incapaz de seguirle la estela a Alemania ni a Francia. Está esperando algo malo, está esperando ver que pasa en noviembre con las elecciones… Del triangulo saldrá o subiendo con fuerza o bajando con fuerza…

Las bolsas americanas llevan unos meses laterales, esperando una digestión de tanta subida…

Alemania prueba:

Y el euro dólar quizás se pueda ir a la paridad, o mucho más bajo después…

Va a haber un movimiento más acusado…

A largo plazo no se gana nada en el Ibex, salvo unos años muy concretos. Ahora no tiene pinta de que vaya a ser el momento oportuno…

Y desde el punto de vista fundamental, los datos son curiosos:

En EEUU el PER esta caro:

Además, sus ventas y expectativas de incremento de beneficios se deterioran…

Divergencias:

A pesar de la rebaja del precio del crudo, ésta no se traslada a los beneficios empresariales:

Los PERs de Europa andan algo caros…

Los mercados emergentes siguen mucho más baratos que los desarrollados:

PD2: A nuestros hijos les hablamos del amor con nuestro ejemplo, pero a una determinada edad es bueno que les contemos nuestra historia: cómo nos conocimos, cuándo nos declaramos, qué hacíamos cuando éramos novios, dónde nos casamos, qué anécdotas recordamos. En fin, se trata de poner la letra a esa canción que ellos van escuchando cada día, esa melodía cotidiana que tararean sus padres al ritmo de la vida.

No nos dé vergüenza rescatar fotos antiguas, leerles alguna carta que guardamos en el fondo de un cajón, escuchar con ellos nuestra canción o enseñarles aquel regalo que tiene un valor impropio de una cosa material, porque lo que cuenta no es lo que se regala, sino quién lo hace y el motivo por que se regala. Es una manera de compartir con nuestros hijos una historia de amor de la que ellos forman parte. En cierto modo, tienen derecho a conocerla, y compartirla es una forma de quererlos.

Pero las historias se escriben renglón a renglón, día a día. Por eso, hemos de hacer visible lo que parece invisible, poner imágenes al texto y texto a las imágenes. Nuestra vida, nuestro transitar cotidiano ha de ser un libro ilustrado del amor, sin grandes definiciones abstractas, sino con acciones concretas que no necesitan notas a pie de página para explicar lo que significan, como:

Ese beso antes de salir de casa.

Ese "qué guapa estás hoy".

Ese vestido que a papá le gustará.

Ese "qué tal estoy" porque vas a buscar a mamá.

Ese "nosotros" que se lee entre líneas.

Ese "nos queremos" que se nota.

Ese día que vamos a cenar solos.

No hace falta esperar a san Valentín para amar y que se note.