En medio de la campaña electoral para las europeas los líderes conservadores que gobiernan y han gobernado Europa durante la crisis han puesto sordina a los problemas para evitar la debacle que les anticipan las encuestas. Pero los problemas siguen.

El ESM, fondo europeo, está negociando otros préstamos para Grecia. ¿Por qué hacerlo en medio de la campaña y no esperar hasta después de las elecciones? Seguramente por qué no hay dinero en la caja. Pero nos lo tenemos que imaginar ya que en esta Europa con déficit democrático los funcionarios de la Troika hacen uso del dinero de los contribuyentes sin dar ningún tipo de explicación y sin asumir ninguna responsabilidad de sus errores.

El mensaje de la Troika y del Gobierno heleno es que Grecia empieza a mejorar. Pero este economista observador se ha mirado los números de 2013 y son estremecedores. El desempleo siguió aumentando, especialmente el juvenil y la pobreza extrema también. Este es el principal drama de la economía griega.

Pero los números financieros son desastrosos. Los talibanes de la devaluación competitiva nos dijeron que bajando salarios aumentarían las exportaciones y disminuiría el paro. Pero las exportaciones de bienes en Grecia acabaron casi estancadas. Sólo crece el turismo igual que en España, por sus privilegiadas islas y playas del Mediterráneo.

Grecia tuvo superávit en la cuenta corriente por que las importaciones volvieron a caer casi un 5% anual. El Gobierno griego le está contando a sus ciudadanos la misma milonga que nuestro gobierno a los españoles. Pero es la depresión y la deflación la que mejoran el déficit exterior.

En la cuenta financiera, la fuga de capitales continúo. En 2013 salieron de Grecia 37.000 mill de inversión de no residentes. Esto fue sustituido por deuda pública con el ESM. Por lo tanto, sigue el proceso que permite a los inversores huir de Grecia y recuperar su dinero y se mutualiza por deuda pública griega. Errores privados los acaban pagando los ciudadanos. Y luego dicen que en Grecia hay riesgo moral. Lo que estamos haciendo con Grecia es una inmoralidad. Si Jesucristo entrará triunfal en Atenas ¿apoyaría a la Troika y al Gobierno griego o al pueblo y los más necesitados? ¿De que moral estamos hablando?

La deuda externa tanto bruta como neta ha aumentado en el último año. Grecia le debe al exterior 420.000 mill de euros. Pero no sólo ha aumentado la deuda externa en euros. El PIB nominal griega se ha desplomado un 25% desde 2009 y con él su capacidad de pago. La deuda externa bruta cerró 2013 en 230% del PIB, 15 puntos más que en 2012. Y la deuda externa neta en 120% del PIB, 13 puntos más que en 2012.

Merkel ya ha conseguido su objetivo. El 100% de la deuda externa neta griega es pública y así sólo necesita negociar con un gobierno débil y no con miles de inversores a los que ampara la legislación concursal griega y la internacional. El riesgo ahora es que Syriza gane las elecciones y se plante. Recuerdo que este economista observador ha preguntado por este riesgo a varios altos cargos de la Troika y no saben o no responden. Si eso pasa no hay plan y lo más probable es que la resolución de la Tragedia griega sería a la Argentina en 2001.

La situación más desconcertante es la del sistema bancario lo cual lleva a pensar a este economista observador que se han inventado todas las cifras de los balances. Hay un dato positivo ya que se ha parado la fuga de depósitos en 2013. Aún así los bancos griegos tienen 50.000 mill más en crédito que en depósitos minoristas y la diferencia se la presta el BCE. Grecia es en si misma un bono basura y los estatutos del BCE prohíben prestar con garantía de bonos basura. Por lo tanto, si Draghi se pone escrupuloso en el cumplimiento de sus estatutos y cierra el grifo, Argentina 2001. Draghi y el BCE han sido corresponsables de los planes de Merkel, sin darse cuenta que ahora son el principal acreedor de Grecia y el problema lo tienen dentro de sus balance. Si Draghi corta el grifo, tendrá que asumir pérdidas millonarias en sus inversiones en Grecia y su comparecencia en el Parlamento europeo no será tan cómoda como la de la semana pasada.

La banca griega reconoce una morosidad del 31,5% y sorprendentemente desde 2010 ha aumentado el crédito a empresas y familias. No es posible un aumento de la demanda de crédito en una país en depresión. Por lo tanto, los bancos prestan a sus deudores para que les paguen los intereses y evitar el colapso.

Si el escenario es Argentina 2001, la depreciación del Dracma estaría próxima al 70% y el supuesto capital de la banca desaparecería como un terroncito de azúcar. Paradojas de la vida, ahora los planes de Merkel favorecen a los griegos ya que sólo tendrían que negociar con el BCE con el que no hay ley concursal y no con miles de inversores como tuvo que hacer Argentina en 2002.

La Troika habla de un nuevo crédito de 10.000 mill pero con ese dinero no llegan ni a final de año. España pagará el 10% de las pérdidas en Grecia. Pero nuestro Presidente sigue en el Cabo de Hornos y mirando encuestas cada día viendo como la gaviota del PP empieza a emigrar.

España en 2014 va a tener el mayor déficit público de la UE 28 y el nuevo préstamo para Grecia se anotará en nuestra deuda pública que van a pagar mis hijos. Así que se acabó. Llegó el momento de la verdad, basta de mentiras y de huidas hacia delante. Acabemos con el riesgo moral y la protección de los inversores internacionales, la mayoría grandes patrimonios. Es necesario un plan para Grecia integral. Y si Merkel no está dispuesta a asumir las pérdidas de manera ordenada con Eurobonos, mutualización y monetización de la deuda, cuanto antes se salgan los griegos del Euro y pongan en orden su balance, antes podrán volver a crecer y a reducir su inmoral tasa de paro y pobreza.

El indicador de eficiencia es la prima de riesgo que en Grecia también ha disminuido. Solo un apunte histórico, en 2001 el 25% de las carteras de inversores internacionales estaba en bonos argentinos, un país que sólo explicaba el 0,7% del PIB mundial y que estaba a punto de estallar. No te fíes de los mercados.

Y Portugal sabemos que tardará 20 años en devolver el 75% de las ayudas recibidas y por tanto seguirá bajo supervisión del FMI y de la UE otros 20 años más…

¿Qué nos pasará en España? Sabemos que fuimos intervenidos aunque no de manera pública… ¿Nos esperan 20 años más que estén pendientes de nosotros? Y tanto…, hasta que no paguemos lo que les debamos a los alemanes, y a todos los bancos (alcanzaremos el 100% de deuda pública sobre el PIB), más el 100% de deuda externa que acumulamos…

Abrazos,

PD1: La deuda global sigue creciendo. Lejos de reducir el problema original de 2008, la crisis de deuda se sigue incrementando, sigue subiendo y subiendo…

While the US may be rejoicing its daily stock market all time highs day after day, it may come as a surprise to many that global equity capitalization has hardly performed as impressively compared to its previous records set in mid-2007. In fact, between the last bubble peak, and mid-2013, there has been a $3.86 trillion decline in the value of equities to $53.8 trillion over this six year time period, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Alas, in a world in which there is no longer even hope for growth without massive debt expansion, there is a cost to keeping global equities stable (and US stocks at record highs): that cost is $30 trillion, or nearly double the GDP of the United States, which is by how much global debt has risen over the same period. Specifically, total global debt has exploded by 40% in just 6 short years from 2007 to 2013, from "only" $70 trillion to over $100 trillion as of mid-2013, according to the BIS' just-released quarterly review.

It should come as no surprise to anyone by now, but the only reason why global stocks haven't plummeted since the Lehman collapse is simple: governments have become the final backstop for onboarding risk, with a Central Bank stamp of approval - in other words, the very framework of the fiat system is at stake should global equity levels collapse. The BIS admits as much: “Given the significant expansion in government spending in recent years, governments (including central, state and local governments) have been the largest debt issuers,” according to Branimir Gruic, an analyst, and Andreas Schrimpf, an economist at the BIS.

It should also come as no surprise that courtesy of ZIRP and monetization of debt by every central bank, debt has itself become money regardless of duration or maturity (although recent taper tantrums have shown what will happen once rates start rising across the curve again), explaining the mindblowing tsunami of new debt issuance, which will certainly never be repaid, and whose rolling will become impossible once interest rates rise. But of course, under central planning that is not allowed. As Bloomberg reminds us, marketable U.S. government debt outstanding has surged to a record $12 trillion, up from $4.5 trillion at the end of 2007, according to U.S. Treasury data compiled by Bloomberg. Corporate bond sales globally jumped during the period, with issuance totaling more than $21 trillion, Bloomberg data show.

Bloomberg also comments, humorously, as follows: "concerned that high debt loads would cause international investors to avoid their markets, many nations resorted to austerity measures of reduced spending and increased taxes, reining in their economies in the process as they tried to restore the fiscal order they abandoned to fight the worldwide recession." Of course, once gross government corruption and incompetence made all attempts at austerity futile, and with even the austere nations' debt levels continuing to breach record highs confirming there was never any actual austerity to begin with, the push to pretend to reign debt in has finally faded, and the entire world is once again engaged - at breakneck speed - in doing what caused the great financial crisis in the first place: the issuance of record amounts of unsustainable debt.

All of the above is known. What may not be known is just who is issuing, and respectively, purchasing, this global debt-funded spending spree, especially in a world in which one's debt is another's asset. Here is the BIS's answer to that question:

Cross-border investments in global debt markets since the crisis

Branimir Grui? and Andreas Schrimpf

Global debt markets have grown to an estimated $100 trillion (in amounts outstanding) in mid-2013 (Graph C, left-hand panel), up from $70 trillion in mid-2007. Growth has been uneven across the main market segments. Active issuance by governments and non-financial corporations has lifted the share of domestically issued bonds, whereas more restrained activity by financial institutions has held back international issuance (Graph C, left-hand panel).

Not surprisingly, given the significant expansion in government spending in recent years, governments (including central, state and local governments) have been the largest debt issuers (Graph C, left-hand panel). They mostly issue debt in domestic markets, where amounts outstanding reached $43 trillion in June 2013, about 80% higher than in mid-2007 (as indicated by the yellow area in Graph C, left-hand panel). Debt issuance by non-financial corporates has grown at a similar rate (albeit from a lower base). As with governments, non-financial corporations primarily issue domestically. As a result, amounts outstanding of non-financial corporate debt in domestic markets surpassed $10 trillion in mid-2013 (blue area in Graph C, left-hand panel). The substitution of traditional bank loans with bond financing may have played a role, as did investors’ appetite for assets offering a pickup to the ultra-low yields in major sovereign bond markets.

Financial sector deleveraging in the aftermath of the financial crisis has been a primary reason for the sluggish growth of international compared to domestic debt markets. Financials (mostly banks and non-bank financial corporations) have traditionally been the most significant issuers in international debt markets (grey area in Graph C, left-hand panel). That said, the amount of debt placed by financials in the international market has grown by merely 19% since mid-2007, and the outstanding amounts in domestic markets have even edged down by 5% since end-2007.

Who are the investors that have absorbed the vast amount of newly issued debt? Has the investor base been mostly domestic or have cross-border investments grown at a similar pace to global debt markets? To provide a perspective, we combine data from the BIS securities statistics with those of the IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS). The results of the CPIS suggest that non-resident investors held around $27 trillion of global debt securities, either as reserve assets or in the form of portfolio investments (Graph C, centre panel). Investments in debt securities by non-residents thus accounted for roughly one quarter of the stock of global debt securities, with domestic investors accounting for the remaining 75%.

The global financial crisis has left a dent in cross-border portfolio investments in global debt securities. The share of debt securities held by cross-border investors either as reserve assets or via portfolio investments (as a percentage of total global debt securities markets) fell from around 29% in early 2007 to 26% in late 2012. This reversed the trend in the pre-crisis period, when it had risen by 8 percentage points from 2001 to a peak in 2007. It suggests that the process of international financial integration may have gone partly into reverse since the onset of the crisis, which is consistent with other recent findings in the literature.

This could be temporary, though. The latest IMF-CPIS data indicate that cross-border investments in debt securities recovered slightly in the second half of 2012, the most recent period for which data are available.

The contraction in the share of cross-border holdings differed across countries and regions (Graph C, right-hand panel). Cross-border holdings of debt issued by euro area residents stood at 47% of total outstanding amounts in late 2012, 10 percentage points lower than at the peak in 2006. A similar trend can be observed for the United Kingdom. This suggests that the majority of new debt issued by euro area and UK residents has been absorbed by domestic investors. Newly issued US debt securities, by contrast, were increasingly held by cross-border investors (Graph C, right-hand panel). The same is true for debt securities issued by borrowers from emerging market economies. The share of emerging market debt securities held by cross-border investors picked up to 12% in 2012, roughly twice as high as in 2008

PD2: Hace unos días fue el aniversario de 5 años de subida de los mercados americanos al calor de los QE:

5 years ago today, the S&P 500 made its post-crisis low at the oddly demonic 666 level. What many may not remember is... the last so-called-at-the-time "secular" bull market lasts exactly 5 years and 1 day (from October 10th 2002 to October 11th 2007)... it's different this time though.

The last "secular bull market"

The current "secular bull market"

En el mercado de bonos se ha producido una nueva convergencia de rendimientos, una sensible reducción de las primas de riesgo, no por la labor de los políticos, sino por un afán de ganar dinero de sus tenedores, los bancos… Y en esta crisis todos los bonos han ganado lo mismo, salvo Grecia:

Daba igual en qué bono se invirtiera, todos han acabado ganando lo mismo.

En las bolsas, las diferencias han sido mucho más acusadas:

Menos el mundo emergente que, a pesar de ser donde hay más crecimiento, que empuja a la economía global, los rendimientos no se han visto todavía en bolsa:

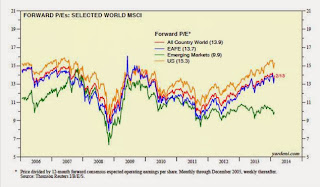

Por lo que siguen más baratos que los demás:

Y en materia de riesgos, los CDS han experimentado una reacción muy similar a la baja. Ya no hay riesgos…. ¿De verdad que todos los bancos son iguales y que todos los bonos también? Ay, qué no es así…

This has been the weakest recovery ever, but it nevertheless has managed to make the U.S. richer than ever before on a nominal, real and per capita basis.

Data released today by the Federal Reserve show that the net worth of U.S. households increased by a staggering $9.8 trillion last year, or by almost 14%. Household net worth is now almost $12 trillion higher than it was before the Great Recession hit. The gains in recent years have come from increased holdings of financial assets (mainly equities, bonds, and savings deposits, which have grown by a total of $21 trillion from their 2009 lows), rising real estate values (up $3.9 trillion in just the past two years), and less debt (down $800 billion from pre-recession highs).

Even after taking into consideration inflation, household net worth has reached a new post-recession high of $80.7 trillion. As the chart above shows, this is very much in line with its 3.7% per year long-term trend growth.

Even after taking into consideration inflation as well as the growth of the population, per capita net worth has reached a new post-recession high of almost $255,000. This figure has been growing by about 2.4% per year for over 60 years. The growth of real per capita net worth hasn't been as smooth in the past several decades as it was in the go-go 50s and 60s, but it has kept up with long-term trends.

Yes, things could be better, but they aren't nearly as bad as you might have been led to believe. The U.S. economy is making a comeback that is fairly impressive

Yes, things could be better, but they aren't nearly as bad as you might have been led to believe. The U.S. economy is making a comeback that is fairly impressive

PD4: Debemos pedir con perseverancia, con insistencia. Enseguida nos cansamos de pedir ya que vemos que Dios no nos lo concede… ¿Nos habremos equivocado en algo? Quizás no se nos tenía que conceder lo que pedíamos… Yo creo que a Dios le gusta más cuando pedimos cosas espirituales que cosas materiales. Y nosotros, torpes, venga a pedir tener más dinero, conseguir aprobar, que nuestro hijo tenga trabajo, que tengamos salud, que nos vayan bien las cosas… Si eso ya sabe Dios que lo necesitamos. Si eso ya está en su mano concedérnoslo… Pero casi nunca nos acordamos de pedir por cosas más profundas, pedir por la salvación de los que conocemos, de nuestros familiares y amigos, pedir para que llegue el mensaje de amor del Señor a muchos que no lo conocen, pedir por el Papa, pedir por los frutos de la iglesia, pedir, por la salvación de uno mismo, pedir por los que están en el Purgatorio… Pedir con humildad, insistir, hágase según tu Voluntad y no esperar a ver los resultados ahora…